SL Interview: John Branch on Derek Boogaard and CTE in Hockey

Derek Boogaard was known as a rugged enforcer in the National Hockey League – the toughest of the tough guys – who had only one duty to perform: use his 6-foot 7-inch, 265-pound frame and lethal fists to protect his teammates on the ice. The lumbering kid from Saskatchewan did his job so well that he was able to sign a four-year contract with the New York Rangers worth a cool $6.5 million.

Derek Boogaard was known as a rugged enforcer in the National Hockey League – the toughest of the tough guys – who had only one duty to perform: use his 6-foot 7-inch, 265-pound frame and lethal fists to protect his teammates on the ice. The lumbering kid from Saskatchewan did his job so well that he was able to sign a four-year contract with the New York Rangers worth a cool $6.5 million.

But the very talent that got Boogaard to the NHL proved to be his undoing. Constant fighting led to injuries to his back, his fists, and his shoulder; he endured multiple concussions. The debilitating pain contributed to Boogaard becoming addicted to prescription drugs. In 2011, Boogaard died due to an accidental overdose of alcohol and painkillers. He was 28. When his brain was examined after his death, he was found to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), due to repeated blows to the head.

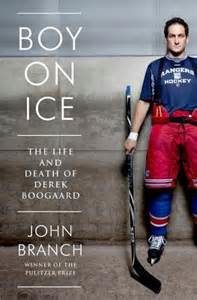

In “Boy On Ice: The Life and Death of Derek Boogaard” (W.W. Norton), New York Times reporter John Branch investigates how playing the macho role of enforcer – and the physical and mental anguish that he endured – brought about Boogaard’s demise. “Enforcers never complained about their role,” Branch writes, “and players rarely admitted to concussions. Enforcers, especially, did not concede to anything that could be construed as weakness or a lost edge. Such an admission raised doubts about an athlete’s commitment and toughness, the most important qualities for an enforcer. To admit to concussions was to commit career suicide.”

Branch goes beyond Boogaard’s life and fistic career to examine how and why fighting has become so ingrained in the culture of professional hockey. He traces the evolution of youth hockey in Canada via the “billet” system, the popularity of websites that “score” the results of each bout and rank each fighter, and the growing consciousness about the threat of concussions among hockey players that parallels what has happened within the National Football League. The result is a cautionary and sobering story.

“Boy On Ice” emerged from deep reporting that Branch did for a three-part article in the Times titled “Punched Out,” which won a Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma. In 2013, Branch was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing for “Snow Fall,” a multi-media effort about a destructive avalanche in the Cascades mountain range of Washington.

SportsLetter spoke to Branch by phone from his home in northern California.

– David Davis

SportsLetter: You wrote a three-part series for the Times not long after Derek Boogaard died. What was it about the story that made you decide that the topic was worthy of a book?

John Branch: I was really pleased with the three-part series. The Times gave me as much room as you could ever imagine for a newspaper story. I think we gave Derek Boogaard as much as a full portrayal as you can in a newspaper. But I was nagged by the fact that there was so much more that I thought could be said, not only about his life and the gaps in his life that we ignored, but also in a lot of the things that we touched on in the series but we weren’t able to go into with too much depth – like, what junior hockey is like, the history of fighting, or even concussions. The series itself didn’t have a whole lot about all the prescriptions that Derek had for painkillers – we didn’t know a lot about that at the time – and it ignored his time in minor-league hockey and his two serious girlfriends.

SL: How would you describe the youth-hockey system in Canada – the so-called “billet” system – that Derek Boogaard went through and that so many young players must navigate?

JB: Hockey is the major amateur sport in Canada. In some ways, their system for youth hockey is not unlike the NCAA setup for football and basketball players here in the States. The big difference is that the kids there are not going off to college or university, and they’re 15, 16, 17 years old, as opposed to 18, 19, and 20.

These are kids who have been told, “Hey, we think you’re a pretty good hockey player. We’d like you to come 1,000 miles from home, live with a new family, go to the local high school and we’ll try to turn you into a great hockey player. At worst, you’ll get a high school education and it’ll be a great experience.” A lot of kids love the idea. A lot of parents love the idea, even though their kids have to leave home at an early age and live in places far from home. They worry about their children: I’m sending my kid to where? He’s living with whom? He’s going to be friends with whom? He’s supposedly going to school, but is anybody checking on his progress?

SL What are the pros and cons of the billet system?

JB: I think the system has a lot of flaws. The travel is brutal. They’re gone for a week or two at a time, several times during the winter, on long road trips in buses on icy roads. Education is not a huge priority. You talk to the people that run those leagues and they say, “Our goal is to make sure that when the kids come to a new team and to a new school their education doesn’t slip. If they were a C student when they arrived, we want to make sure they’re still a C student.” But a lot of the guys never graduate from high school. The way the schedules are usually set up, they cram all of their classes into the morning, so they can be free in the afternoon for practice. That’s not necessarily a good thing when you’re talking about 16-year olds. They’re required to go to class, but no one is checking in on them to make sure they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing.

I think we’re seeing, more and more, the question of safety on the ice with concussions. That was not part of the concern even for the Boogaard family as recently as 10 or 15 years ago. It used to be that the ice was the safe spot, and parents worried about what their kids were doing away from the ice. Now, parents are starting to worry about the health of their kids on the ice.

SL: Is fighting allowed in youth and junior hockey? Is the penalty for fighting different in those leagues than it is in the NHL?

JB: It’s not much different in the major-junior leagues than in the NHL. It’s the same penalty: five minutes for fighting. The top three leagues have not changed their rules, although they have increased the penalties for staged fights – like, if they start fighting before the puck’s even been dropped in the face-off circle.

But I think the sentiment is shifting towards the safety of the kids. The president of Hockey Canada, which oversees the three major junior leagues, has stated that there is a need to move fighting out of the game because it’s become a public safety concern for kids who are 16 and 17 years old and maybe don’t have a true choice in the matter. I think they’re realizing that, if 28-year-old millionaires playing in the NHL want to beat each other up, that’s one thing.

At the lower levels below the major junior leagues, they have recently increased the penalties for fighting. They’re now an extra 10 minutes in some leagues and game misconducts in other leagues. Basically, it’s percolating its way from the bottom up. These are trial efforts. They’re going to go for a year or two and see how that works. Do the fans still like it? Are there fewer fights and, if so, are they seeing fewer concussions and fewer injuries? I think if it succeeds, then they’ll probably start putting more and more of those type of penalties into the top level. And, who knows? Maybe it keeps working its way all the way up.

SL: Derek Boogaard was known for fighting, for being “a goon.” When did goons emerge as a roster mainstay in the NHL?

JB: Fighting has always been part of the NHL. I was just reading a biography about Gordie Howe, and it mentioned the “Gordie Howe hat trick:” a goal, an assist, and a fight.

In recent times you can trace this back to the Boston Bruins and the Philadelphia Flyers – the Broad Street Bullies – in the early 1970s. They created this play-tough-and-nasty-and-win era. Then, in the 1980s, it evolved where teams had more of a singular enforcer, the Marty McSorleys of the world, someone who could be the bodyguard for Wayne Gretzky. He was more of a personal protector. That started maybe 20 years of these one-dimensional, large enforcers. Derek was probably among the last of that breed.

I think we’re starting to see the pendulum swing back toward guys who can play more minutes on the ice, but who are also willing to fight as needed. So, instead of having one guy with 20 fights, you might have four guys with five fights.

SL: Beyond the physical aspect of fighting in hockey, what are some of the unique pressures that enforcers like Boogaard have to deal with?

JB: I’m not even sure their own teammates and coaches understand this. I didn’t understand this, and I covered hockey for a few years, and that is the internal pressure that these guys feel. They’re usually the lowest-paid guys on the team. They’re at the bottom of the roster, and they feel they can be replaced at any time because of that. They always know there’s someone else in the minor leagues that can take their place if they lose the next fight or are somehow embarrassed in a fight or get hurt. And, they can’t show this fear, this concern, because they’re paid to be the macho guy. They’re the bodyguard, the guy that everybody else looks up to be the toughest guy around and to stick up for them. So, they have to put on this persona.

I think we in sports media have done a great job of caricaturizing that role and not looking very hard at what these guys go through. But when you hear someone like [retired enforcer] Georges Laraque tell you that there were times when he couldn’t sleep at night, or when you hear guys say that they would go to the movies in the afternoon and walk out without any idea about what they just saw, it’s because they were worried about the next fight.

They’re under this strange pressure because there are times when they don’t know when the next fight will come. They’re thinking, “We’re winning 5-0. I’m going to have a great time sitting on the bench,” and then suddenly the other team puts out its enforcer, and they’re expected to immediately build up enough anger to go out and fight the guy and prove themselves to their teammates.

Sometimes – and this is almost worse – they do know when that time’s going to come. They know that, after what happened in the previous game with, say, the Oilers, the next time they play, they’re probably going to have to fight their guy again. So, they know there’s a date three weeks from now that they’re going to go. There is nothing else like it in American sports.

SL: You write that, in the NHL, fighting is considered “necessary to control violence” and a healthy “outlet for aggression.” How did we get to this point?

JB: That’s the rationale that hockey people will give you. It’s not necessarily my opinion. But that came about because hockey is a fast sport and it’s a violent sport. One hundred years ago, when some guy whacked you with a stick, your only way to get back at him was to beat him up. So, it started as a little bit of vigilante justice. The threat of me beating you up, or one of my teammates beating you up, would hopefully temper your nastiness and your actions.

There’s not a lot of proof that allowing two guys who have nothing to do with the incident in the first place to stop the game and fight will keep other guys from doing anything else. It’s all anecdotal evidence. I think it’s an argument that’s pretty weak, and now we’re starting to see the serious flaws in it.

SL: Why did it take so long for the danger of concussion to get on the radar of professional hockey?

JB: NHL people will tell you that they were the first major sport to have a concussion protocol, that back in 1996 they were recognizing that concussions were an issue and that they needed to take players off the ice and examine them. They think they’re very forward thinking on the issue. Where they struggle, I think, is how they can say they’re taking concussions seriously when they allow two guys to beat each other in the head while everybody stands back and watches. That’s a tough argument to make.

The NHL, as much as they’d like to say they take concussions seriously, never explained to Derek Boogaard what a concussion really was. No one told him that, those times when he blacked out or when he got punched in the head or fell and hit his head or whatever, that those were concussions and that they were all going to be potentially adding up. If the guys who are fighting can’t tell you what a concussion is, then I don’t think you’re doing all you can for concussions.

Derek’s family, who saw him every summer and knew that he was struggling with injuries, never worried about concussions. That wasn’t part of their concern. They were worried about his hands, they were worried about his back and about his shoulder that he kept having trouble with. No one thought about the concussions, and that probably includes Derek.

SL: When did the perception change that repeated blows to the head, even ones that do not seem traumatic, are as potentially dangerous as that one crushing blow?

JB: In some ways, we’re in a very scary time where we know enough to be frightened but maybe not enough to make rational decisions. The thing with CTE, which [New York Times reporter] Alan Schwarz wrote about and which doctors have been studying for many years now, is that they don’t believe it’s caused by those big concussive hits. They believe it’s caused by sub-concussive hits. In other words, you don’t even have to have concussions to end up having this disease. Which is why we’ve seen this, historically, in the brains of boxers and why we’ve seen it in 80-some brains of former NFL players. Every time you crash into someone on the offensive line, maybe that’s enough to cause one of those sub-concussive hits that eventually adds up.

We tend to focus on the giant hits – the wide receiver who gets clocked going over the middle and has to be carted off. Those are certainly dangerous. But I don’t think we’ve quite figured out the impact of all those small hits and why certain people will have serious damage down the road.

SL: The level of machismo in hockey – the pain threshold among the players – is known to be abnormally high. Do you think NHL commissioner Gary Bettman is afraid to anger hockey traditionalists by not taking a stronger stance against fighting?

JB: I think it’s an economic issue at its heart. I think one of two things will happen. Either the lawsuits will continue to add up – and there are a lot of former NHL players lining up now in a class-action lawsuit against the league concerning concussions – and the NHL will realize that they’ll have to spend a lot of money to make these lawsuits go away, the way the NFL did, or they’ll have to fight the lawsuits. Either way, that won’t be good for the game.

Or, secondly, they’ll realize that the public perception is, fighting is barbaric. But right now, fighting sells. The NHL will tell you that the fans like it: just look at their sold-out arenas and the fact that they’ve never been financially stronger. Until that’s threatened, perhaps by the issue of concussions, they’re not going to make a big move about fighting.

SL: Is Derek Boogaard’s family involved in this effort?

JB: So, the Boogaard family has filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the NHL. The wrongful death lawsuit has more to do with the prescriptions and the care he received from doctors and the substance-abuse programs than it does concussions. The evidence is more tangible. In other words, it’s hard to know exactly what role concussions played in the death of Derek Boogaard, but they do know how many pills he was given and what the notes of the doctors and the counselors said in the months and years leading up to his death. That lawsuit is working its way through the justice system. It may take a long time to settle or go to trial.

There have been three lawsuits filed against the NHL that have more to do with concussions, filed on behalf of former NHL players who say they are struggling in retirement, much like former NFL players. Those three lawsuits have now been consolidated into one class action lawsuit in Minnesota. I’m told by the attorneys that are overseeing the case that there are about 200 former players lined up to join that lawsuit so far. The lawyers think that, if in the next year or so they can get 500 or more players involved, there will be a tipping point with this issue. I think the arc of this is following the NFL situation over the last five or six years.

SL: If you were the commissioner of the NHL, what would you do about fighting in hockey? Should fighting be banned or more heavily penalized?

JB: In the book I avoided stating my personal thoughts on fighting. I tried to just lay out the facts about Derek’s life. I would like to think that if I was the commissioner, I would say, “Let’s get all the facts. Let’s bring all these different groups of people in and find out what’s the best thing for this game and for the health of the players.”

You would like to think that the commissioner of a sports league would be the grownup in the room and say, “Can we at least have this discussion?” Perhaps those discussions are taking place behind closed doors, but the perception from outside those closed doors is that hockey and the NHL doesn’t care and is very dismissive about this.

SL: Commissioner Bettman comes off as willfully naïve in the book with his dismissal of CTE. Will this be part of his legacy: that he let fighting in hockey continue at a time when the dangers of concussions were known?

JB: I think it will threaten his legacy. His arguments with CTE sound a lot like Roger Goodell about five years ago. The NFL didn’t pay a whole lot of attention to the issue and dismissed the science for a long time until there were about 17 or 18 former players whose brains were examined and found to have CTE. For whatever reason, they suddenly said, “Maybe we should sit down and learn more about this and talk to these doctors.” They changed their tune. They’re now running commercials during games telling parents how to watch for signs of concussions with their kids. A cynic would say that the NFL realized this was horrible PR for them and so they’re trying to get ahead of this.

I believe that, so far, four former NHL players have been found to have evidence of CTE. The doctors at Boston University who have worked on this would say, “How many brains does it take for you to sit down with us and try to find the answers to this problem and not be so dismissive of the science?”

SL: What most surprised you in researching the book?

JB: Two things. The main reason I wrote the book was to fill in all the gray areas of Derek’s life because the enforcer might be the most cartoonish character we have in sports. I wanted to pull back the curtain and, using Derek’s life, show people what these guys are like. But I think even I was surprised about what they go through and what their real lives are like beyond the caricature of what we see on the ice. They seem to be very simple guys, but they may be as complex as any athlete in pro sports.

More specifically, I was surprised by the volume of prescriptions that Derek had during his career – and the effort that went into keeping Derek on the ice and the number of people who were involved in prescribing him pills, with apparently not a lot of communication between them. I think hockey and all other professional sports need to take a hard look at their team doctors and the people who care for the athletes. That includes, once the athletes get addicted to prescription pills, their substance-abuse programs.

The lawsuit filed by Len Boogaard, Derek’s father, addresses this. Hockey has a structure in place to bring these guys up and to get them on the ice. But once they start to falter, there seems to be a lot of holes in that structure.

SL: Do you have plans for a next book?

JB: No, I need to get back to my day job at the newspaper. But the issues that were raised in the book aren’t going away. So I wouldn’t be surprised, in the next year or two, if my byline is not on a few stories that have to do with these topics.