SL Interview: McFarland USA’s Coach Jim White

In 1987, the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) held the first high school state cross-country championship meet. The Division IV winner was an unheralded team from McFarland High, a small school (about 750 students) in a small town in the San Joaquin Valley. Coached by Jim White, the Cougars were entirely composed of Mexican-American boys, a reflection of the demographics in the town itself. Many of the students also worked in the nearby fields, picking grapes and almonds with their parents, even while they attended school and clocked training miles.

In 1987, the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) held the first high school state cross-country championship meet. The Division IV winner was an unheralded team from McFarland High, a small school (about 750 students) in a small town in the San Joaquin Valley. Coached by Jim White, the Cougars were entirely composed of Mexican-American boys, a reflection of the demographics in the town itself. Many of the students also worked in the nearby fields, picking grapes and almonds with their parents, even while they attended school and clocked training miles.

White and McFarland were just getting started. The Cougars went on to win nine state cross-country titles in 14 years, establishing a distance running dynasty in Kern County. Many of his students were able to parlay their running prowess into college scholarships. Their victories helped a town in need of some positive news: about the only story coming out of McFarland since the 1980s concerned a mysterious “cancer cluster” that plagued the area.

Soon, this remarkable story of determination, pride, and love began making headlines outside of the running community. Marc Benjamin, a reporter with the Bakersfield Californian, was the first mainstream journalist to write an in-depth story about Coach White and his hardscrabble runners (who delighted in calling him “Blanco”). That feature was published on November 29, 1996. Almost exactly a year later came a gripping, front-page story written by reporter Mark Arax of the Los Angeles Times, who trailed Coach White when he jumped on his bicycle and pedaled alongside the runners weaving through the vineyards.

In 2004, Gary Smith, the longform wordsmith at Sports Illustrated, followed with an extended feature about McFarland. “No one can figure it out, how the runners with the shortest legs and the grimmest lives began winning everything once Blanco took over the program in 1980,” wrote Smith.

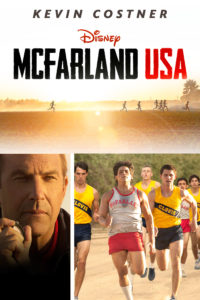

This year, Disney turned the feel-good story into a heartwarming movie titled “McFarland, USA,” directed by Niki Caro and starring Kevin Costner as Jim White. The film, which is advertised as being “based on a true story,” manages to stay true to McFarland’s authentic spirit, even as it strays from the literal truth. “Predictable and predictably rousing, this inspirational sports pic earns points for its big-hearted portrait of life in an impoverished California farming town, the likes of which we too rarely see on American screens,” wrote Variety’s Justin Chang.

SportsLetter spoke by phone with coach Jim White, now 73 and retired, about coaching youth sports and about the new movie.

–David Davis

SportsLetter: Had you ever coached track and/or cross country before you started the program at McFarland High School in 1980?

Jim White: Yes, I had because I was doing age-group stuff in elementary and junior high. Back in ’74, we started our own little track club so I could take kids to different meets. I took them to the national meet, I took them to Oregon. Things like that. I never coached at the high-school level until 1980. So, Damacio Diaz and Johnny Samaniego – who are two of the kids featured in the movie on the ’87 team – we coached them and took them to Oregon when they were younger.

SL: The movie condensed the story for dramatic purposes, of course, and it depicted you arriving in McFarland in 1987. But you had been living there awhile, right?

JW: Yeah, that was so Hollywood because we were there starting in 1964. That’s when we became part of the town.

SL: Were you from the area – central California – originally?

JW: I was raised in Stockton. I went to school three years in Idaho – that’s where they came up with the idea of Kevin Costner moving from Idaho to McFarland. I never did teach or coach in Idaho. My first teaching job was fifth grade in McFarland in 1964, right after I graduated from Pepperdine. I started coaching at the same time. I always coached something – elementary, junior high, recreation.

SL: Were you a runner?

JW: No, I was a baseball and basketball player. I wanted to coach baseball in high school. That would have been my first choice. My first choice got changed pretty quick. They had a team, but I never was allowed to get involved in the high school program over there because there never was a position for me. You had one P.E. teacher – and he was always the football coach. That’s the small school setting. They didn’t take walk-on coaches.

SL: How did it come about that you were able to start coaching cross country at McFarland High School?

JW: In 1978, they had two kids in the program. So, they dropped the program. In 1980, our town pulled away from Kern County school district, and we became part of the McFarland school district. The athletic director at the time committed to have cross country, but then she left and there was a new athletic director. He offered me a position helping him coach football at the high school. I did it one year, as an assistant, but I wasn’t really interested in it. I said to him, “I’d like to have the cross-country program and the track program at the high school.” He said, “We don’t have a cross-country program.” I said, “If you go back to the minutes of the meeting and look at the commitments the school made that were passed by the board, we’re supposed to have one.” He called me back and offered me the position. I said, “What do I have to do to build a program and keep a program?” I didn’t want to start something, and then all of a sudden they want to drop it. He came up with a number of ten. He said, “If you can get 10 kids to come out, we’ll have the program going.” The first year, I think I had 19 kids. That started the program in 1980. I had the track program, too, starting in 1981.

SL: How did you learn to coach cross country? Were there books or instructional manuals that you leaned on?

JW: I looked at a lot of training videos. I went to several coaching clinics – didn’t matter who the coach was or who the speaker was. I was just trying to absorb all I could because I never was a runner. I used to try and volunteer to help the track team at the high school, because my eighth-graders were going over and beating the high school kids. But when they became freshmen and sophomores, there was never any development. They weren’t getting any better. It was, “Just go out and run.” Their long-distance program for the milers and two-milers was: Monday, Wednesday, Friday – you run two miles. Tuesday and Thursday – you lift weights.

SL: Were there any particular coaches and/or runners who gave you advice?

JW: Not really. I picked up a few important things on how to make my program a little more visible through Joe Newton, out of Chicago. He had won several championships, and he used limos and tuxedos to get the kids excited about running. So, I started doing that, too. I started dressing the kids in tuxedos for our award banquets. I picked them up in the limos. Things like that. I paid for everything.

SL: How did your coaching style evolve – and how did your workouts and training regimens evolve?

JW: With me being an inexperienced distance coach, a lot was trial and error: What can the kids handle? How much can I put on them? We developed some of this year after year. We found that summer running is the key. You’ve got to put in the time and the distance, you’ve got to build a large base or you can’t improve.

Some of my philosophy in coaching came from my own experiences. I had a couple of bad experiences – one in high school, one in college. I never felt like I was given a chance for one reason or another. I always felt like I was good enough, but not given the chance. So, I wanted to make sure that I gave everybody that chance that I didn’t get.

When I started the recreation track club back in ’74, I was asked by a parent if I would work with their son. He wanted to run the hundred. I said, “You’re the fastest in your grade. You’re probably the fastest in your school at your age. But when you leave McFarland, you will no longer be the fastest. I can look at you and tell. But let’s take your speed and, if you’re willing to work, let’s do the 400.” So, that’s what we did. We turned him into a 400-meter man and took him to the junior Olympics in Denver, Colorado, and he came in second. It’s just hard work. I was willing to take one kid, two kids, three kids if they’re willing to work and try to get better. That’s what I concentrated on – the kids.

It was easier to do that in cross country and track. You know, I did coach baseball in junior high in McFarland. And what happened was, my pitcher would still be picking potatoes when the game started. Or, my catcher didn’t show up because he’s working in the field. One guy, two guys – there goes your whole team. With track, if your 400-meter man doesn’t show up he only hurts himself. He doesn’t hurt the whole team.

SL: When did you realize that the hardships the kids in McFarland have to go through – working in the fields, for instance – might be an advantage?

JW: It becomes an advantage if you can build on that attitude. These kids are good kids. They’re hard workers. They had to understand, hey, look at what I did in the morning, working hard in the fields. Now I’m out here running in the same fields in the afternoon. If they can adapt to that, and trust in what we have to offer, it’ll work out.

SL: Looking back, what were the biggest challenges that you had to overcome in terms of building the program? Was it getting the kids to buy into the program? Was it the usual temptations that teenagers face – like gangs and drinking?

JW: You probably named them all. One of the things I told them was, “You gotta leave the girls out. Because if you’ve got a girlfriend, the next thing you know is that you gotta get a car. If you get a car, now you have to have a job. You don’t have time to do what we need to do. So, let’s put all that aside right now and get to work.”

SL: Do you speak Spanish?

JW: No, I don’t. Just terms and phrases.

SL: Was that ever an issue?

JW: Language was never a barrier because there was always somebody out there who can translate. I had a few kids who didn’t speak too much English, but they were more shy than anything else because their English didn’t sound like the next boy’s.

SL: What about funding?

JW: That was a challenge. I found myself being a fundraiser all the time, raising money to help put shoes on their feet, to give them money for lunch when we stopped at Taco Bell or McDonald’s. Some of the kids would sit on the bus and say, “I’m not hungry.” Well, I know they were hungry, but didn’t have any money. I’d say, “Here, take this and buy your lunch.” That was always a continual thing – and it still is.

My wife and I became like second parents to the kids because we provided a little extra money for them. We provided the shoes for them. We provided T-shirts. I had sayings every year, sometimes in Spanish. It could be, “Si se puede.” Or, “The road where nobody’s been.” “Champions train, losers complain.” They ended up with three or four T-shirts every year. I said, “You’re going to represent your team, your community, your school, your family, so I’m going to give you something that makes you look good. You’re going to dress nice. You’re not going to wear that ‘wife-beater’ thing out in public.”

There’s a scene in the movie where our name was misspelled on the hats: “Cougars” was spelled with “-ers.” That actually happened, but it was on our sweats, not the hats. The athletic director said, “Jim, you need to learn how to spell.” I said, “I told you to order some sweats. It’s October, we’re just now getting the sweats. Do not send them back. We’ll use them.”

SL: What was it about coaching that you most enjoyed?

JW: Dealing with the kids and watching their progress. Feeling that we had some influence, in a positive way, on their lives. I loved working with the kids. We had a small group of kids – some 20 or 30 every year – but we had a closeness. We built a bond with them. They become like family. They come to our house. They help me mow the lawn or they help me wash my car. They just pitch right in. They’re part of our family.

We still go to a lot of the family functions in McFarland. Mr. and Mrs. Diaz have a family function, with well over 100 people, once a month. Well, we’re included in that. We go to their church camp and help them with the activities. There were seven Diaz kids. All six boys ran for me, and so did their one girl. The best team [the girls had] was third place at state, and she was on that team. Of their seven kids, six of them are teachers. I think five of them have their Masters.

SL: Did you start the girls cross-country team at the same time as the boys and did you coach them as well?

JW: Yes, I did. I started the girls program the very first year – 1980 – with two boys teams. We had a frosh-soph team and a varsity team. I didn’t coach the girls my entire career. I had the girls from ’80 to’85. In 1986, I went to the athletic director and said, “Hey, I need some help. I’ve got beginning girls, advanced girls, beginning boys, advanced boys. I don’t do this on a track. I’m out in the country, on dirt roads and in the orchards. Can they get me another coach?” So, they got me a coach for the girls in 1986, and that was the year we had two girls killed on the road, hit by a car, during practice.

SL: How much support did you get from the school and the school district?

JW: Many of the hardships we had came from within our school – or within the school district and the superintendent’s office – not from the community. The families were very supportive. They knew me because I’d been there so long. I had their kids, then I had the kids of their kids.

I said, “We’re gonna do it my way because, for us, that’s the right way.” As long as we’re continuing to do things the right way, it didn’t matter what anybody said. The principal didn’t want us to go overnight to Mt. SAC, but he allowed us to. He said, “Why do you do these things?” I said, “Because they have never done this. These kids never had the opportunity to travel, to see what a college looks like.” He said, “Why do you take them to a fancy meal?” I said, “Because they’ve never done it.”

And so, you offer things like that. We took them bowling, we took them to movies for the first time. It’s a little different now. They have some of these things available to them. Back then, they didn’t. Their parents couldn’t afford it. Mr. Diaz never saw any of his kids run a race. Never, because he was in the fields working and providing for his family.

SL: How did the school and the city celebrate the success of the team?

JW: When we first started winning at state, I couldn’t get our accomplishments put up in our own gym. They wouldn’t allow that. I talked to the principal and said, “Why don’t we get some banners put up for the team championships?” He said, “No, no, we can’t do that.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Well, because your program makes all the other programs look bad.” I said, “It might inspire them to do something different if you can recognize them.”

All the state plaques were stored away and stacked up. You couldn’t even see them. Some of them were in a custodian’s room or kept in boxes. We had a new superintendent who came in, and now it’s totally different. We have more recognition. We have a trophy case. There’s the state championship banners hanging from the front of the school gym.

People started to embrace this, almost like a movement. Our city logo has changed. It used to be that the logo was “The Heartbeat of Agriculture,” and we had some cotton and flowers on there. Well, we don’t even raise cotton anymore. Now our city logo is a silhouette of a runner, running through the fields, and underneath it says “Tradition, Unity, Excellence.”

SL: You told me that you’ve seen the movie several times. What part of the movie do you most enjoy?

JW: I don’t know if there’s a “most.” There’s parts that bring out more tears than others. The first time we went to see it, we went in with an attitude that, “Look, we know it’s not a documentary. We know there’s going to be a lot of things that are Hollywood.” But we loved the movie. We’re very, very positive about it. The first 13 times I saw it I cried. The 14th, I was able to keep myself together. I just went to see it with some friends in Fresno, and I cried again. It’s the family spirit that we had as a team.

SL: As you mentioned, the film isn’t a documentary. I wanted to ask you about the scene in the movie showing a prison right next door to the school. Is that accurate?

JW: There’s now three of them – one women’s and two men’s – but they’re not quite that close. They’re about a half-a-block away.

SL: How about the climactic race in the movie – the 1987 state championship meet – that was filmed in Griffith Park. Did that happen here in Los Angeles?

JW: No. That race was held in Woodward Park in Fresno, where the CIF cross-country state championships have been held every year since 1987. We have run in Griffith Park, at the Bell-Jeff Invitational event.

SL: How about the Diaz brothers depicted in the film: were three brothers on the team in 1987 and was their mother so adamant about them continuing to work in the fields?

JW: It’s true that all three [David, Damacio, and Danny] ran on the 1987 team in the movie. Their mother was a slave-driver. When the family saw the film, her husband said, “Oh, she was meaner than that.” Her son Damacio, he’s a detective now. He said, “If someone reported what they did to us nowadays, I’d have to arrest them.”

SL: Did you drive the kids to the Pacific Ocean?

JW: Yes, because they’d never been there. One time we came over the hill on the bus and you could see the ocean out there, and a boy said to me, “Mr. White, what’s the name of that lake? That’s huge.” They didn’t have a clue, some of them.

SL: I understand that you retired from coaching and teaching in 2003. Do you and your wife still live in McFarland?

JW: We have a house there. We have another place in the mountains – east of McFarland about an hour – where we spend most of our time. I did some volunteer assistant coaching at McFarland the last two years.

SL: What is it like for you to follow the team today?

JW: Every program in McFarland that has running is coached by one of my kids – the junior high, the elementary, the recreation. The girls coach at the high school ran for me, the boys coach at the high school ran for me.

SL: Do people complain and ask you, “Why hasn’t McFarland won state recently?”

JW: You know what they’ve done to us? They’re punishing us. They’re keeping us from winning our section championship and having a chance to win state. About five years ago, they moved us to Division III. We took first and second the next two years, and then they moved us to Division II. In our section we beat all the Division II schools. We could compete in the Central Section, but couldn’t compete in state at that level. In the last five years we could have had three more state championships. Then they moved us up again. We’re now in Division I. This year was the first time we didn’t go to state in 24 years. That made them happy.